MRCO BLOG

Medical Musings, Health Hypotheses & Therapeutic Thoughts

|

Osteopathic telehealth, that is, consultations over video conferencing (Skype is a well-known example), is a bit of a tricky one. Osteopathy is rightly known and appreciated for its strong hands-on component, ‘magic hands’ that go a long way towards alleviating a sore back or twisted knee. So how does telehealth for osteopathy work? Thorough History & Assessment Osteopathy is more than the combination of skilled practitioners and manual techniques. The founder of osteopathy (A. T. Still) said that “Osteopathy is a philosophy”, meaning that is is more than a treatment - it is a way of looking at the individual as a whole, rather just the sore area. Over a video call, osteopaths take still a thorough and detailed history by asking you lots of questions. In asking you to perform certain movements and carry out some simple tests, we can actually get a lot of information about what may be going on. From our video assessment, we will be able to work out if your issue is something that you can self-manage in your own home, or whether you need to have further investigation done by going in to see a medical doctor (or osteopath, when it is safe to do so). Exercise Management ProgramYour osteopath can give you relevant exercises that you can perform at home, while maintaining your physical distancing measures! Most of my patients will know of my strong interest in, and support of, self-management, and I feel a very bittersweet smugness at knowing that those I have seen over the last seven years will be as well-prepared as you can be for self-management over a potential coronavirus lockdown. I often pose to my patients the hypothetical question “what happens if you can’t see your osteopath??” as part of my rationale for giving you all so many exercises! Even without the face-to-face assessment and treatment that people rightly associate with osteopathy, we can still help you to manage your issues in these uncertain times. No-one under lockdown can complain about not having enough time to do their self-management strategies! Lifestyle Advice It is important to recognise that poor sleep, nutrition, work/home stresses and strains etc. contribute significantly to the sorts of problems people come to see an osteopath. It's not hard to see how the stressful environment we are living in my contribute to our pain!

Osteopathy is a university degree/honours level program, and in the course of the extensive training we will cover nutrition, over-the-counter and prescription drugs, sleep and breathing issues, and a host of other related areas of theory and practice. Osteopaths can offer general advice and, if necessary, refer out to appropriate specialists (if we feel any of these issues are impacting on your presenting problem) while keeping to our areas of competence and expertise. For those of you who don't know how I feel about professionals of any stripe who do that, head over to our blog to find out! So if you have an issue that has been bothering you, why not book an online telehealth consultation with your osteopath today, and get some practical advice on what you can do? Dr. Edmund Bruce-Gardner

The human hand is such a sensitive and specialised structure; anatomically complex and strategically engineered by time and nature, having the ability to create such varied and precise movements. Our hands contain so many weird and wonderfully specialised sensory cells that function to collect information via touch, position, pressure or temperature in relation to our current surroundings. The information is continuously relayed to our brain where the appropriate networks of neurons pass precise instructions via the spinal cord, neural networks and down the nerves in our arms to the muscles responsible for generating the gestures we require. This intricate sensory/motor control system is continuously checking itself and making small adjustments. We could be typing away in an attempt to conquer the monstrous, multi-headed hydra-like inexhaustible queue of office emails, operating an electric sander to remove tired paint in an effort to restore an antique to its former glory or just the general lifting and carrying as we go about our everyday activities. With all these moving parts and capabilities made possible with our hands, we can create works of art and express ourselves. .

When we’re limber and feeling good, we barely notice how much we rely on and require that normal baseline level of ease. However, when things don’t go as planned and if an injury occurs, whether caused by simple tasks or other health conditions, the loss of our normal function is very apparent. One possible common condition responsible for hand pain is Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS). It affects 4-5% of the population (1) and can be quite disruptive, affecting a variety of people, from pregnant women, office workers and the elderly, to tradesman and others who work directly with their hands. It seems to be caused by multiple factors, which could include (2);

Many of the structures that operate the hand are sandwiched together and must pass through a channel at the wrist (the carpal tunnel) bordered by sturdy carpal (or wrist) bones and ligaments, particularly the transverse carpal ligament as the ‘unyielding ceiling’. Most of the space in this channel is occupied by rigid tendons that control finger movements, leaving only a small potential space for the squishy median nerve, which can be easily compressed here (1, 2). Being the main sensory and motor supply for the palm of the hand, a squished median nerve can result in the frustrating and restrictive experience that Carpal Tunnel Syndrome is known for. If you are experiencing signs and symptoms such as those described, the best course of action is to consult your GP or manual therapist as early as possible. This could limit the impact on your everyday life activities and the need for any interventions in future. If CTS is left to progress, a cortisone injection may be beneficial. It was reported that approximately 75% of patients experience improvement following this procedure (4, 5). Failing that, a small surgical procedure can be recommended. It involves releasing the transverse carpal ligament (the mentioned ‘ceiling’ of the carpal tunnel), creating more space for the muscle tendons to glide together at the wrist, alleviating the direct pressure placed on the median nerve. Luckily surgical intervention for CTS has a very high success rate, with over 90% of patients reporting alleviation of symptoms (6, 7, 8), However, it is important to remember that as far as your body is concerned, there is no such thing as 'minor' surgery! Even in the best case scenario, the carpal tunnel now has (even more rigid and unyielding) scar tissue around it, which can cause other issues. So the best thing to do is avoid any intrusive interventions. And it’s entirely possible!

Along with osteopathic techniques for treatment, there are some simple and inexpensive things to try, some examples include (2, 3);

Developing an understanding of how and why this is happening; knowledge alone can alter the experience and help settle the worry. Being informed is a powerful position to be in as you can select the best course of action and knowing what the possible benefits or disadvantages of the available options are. CTS can be debilitating and impact negatively on your health and wellbeing and day-to-day activities. That’s why getting treated as soon as possible is so important. By finding the right combination of strategies that are best for you, your osteopath can get you moving and back into your daily routines, whether it be gardening, writing, creating a masterpiece, or tackling a home renovation. Not to mention going back into battle with inexhaustible email queues – the multi-headed hydras! References:

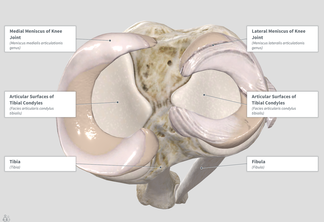

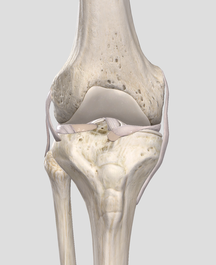

Dr. Edmund Bruce-Gardner The knee is a pretty badly-designed joint. Evolution doesn't move towards perfection, but function. As bipedal (two-legged) creatures who evolved from quadrupedal (four-legged) ones, quite a few compromises and fudges have been made. [The shoulder is another good example. it is a heavily-modified hip (i.e. ball-and-socket joint), but one where the bony shape and supporting ligaments have to allow for such a large range of motion that it relies on the surrounding muscles for nearly all of its support and integrity, as well as on the function of all the other joints surrounding it. You can read more about the weird and wonderful world of the shoulder complex here.] But anyway, the knee... It is a hinge joint, the largest joint in the body, sandwiched in between the two longest bones in the human body, the femur (thigh bone) and tibia (shin bone). This is a fairly bad idea to start with, because long levers generate a lot of force. Worse, it's not a very simple hinge joint. If it were, and could only bend forwards and backwards, and we wouldn't be able to walk on broken or uneven ground. So we have the longest bones (/levers), generating a huge amount of force, going into the largest joint, which is also extremely complex.  Doesn't look massively stable, does it? Doesn't look massively stable, does it? Back when we put all of our weight through four ‘knees’ instead of two, this was less of an issue. We also tend to weight-bear with our knees more or less unbent. This provides a lot more opportunity for trauma. Contrast this with other mammals such cats, dogs, horses, chipmunks, etc. etc. The bottom of the thigh bone is a bit like the cartoon version of a bone, with two knobbly bits (called condyles) at the bottom. These then (theoretically) meet, or articulate, with the relatively flat top of the shin bone. This works about as well as you would imagine.  Evolution’s workaround here was to put these two sort of cups, called menisci, on the top of the flat bit of the shin bone (rather poetically called the tibial plateau). These allow the knobbly condyles to sit a bit more firmly on the top of the tibia. Now, of course, we have another structure that takes a lot of force, and can get injured. Most sports fans (not to mention players) will have heard of a torn meniscus. I tore mine when I was about fourteen, and still remember it as one of the most exquisitely painful experiences of my life. As you can see in the diagram above, when the menisci (the 'C-shaped' things around the outside) are in place they cover most of the top of the tibial plateau.  Here you can see the collateral ligaments (on the sides) and sneak a peek of the cruciate ligaments and menisci (between the femur and tibia) Here you can see the collateral ligaments (on the sides) and sneak a peek of the cruciate ligaments and menisci (between the femur and tibia) But wait! There's more! It's not all about the menisci. In a flash of evolutionary genius, the other main way that the knee is stabilised is by four... ...elastic bands, Well, not literally, but they might as well be. The rubber bands (known as ligaments by the medical types) are actually just thickenings of the capsule that surrounds the joint. Again, sports buffs will probably recognise the terms medial and lateral collateral ligaments. These refer to the ligaments on the inside, and outside, of the knee, respectively. The anterior and posterior cruciate (or 'cross-like') ligaments go between the femur and tibia, and can be seen (along with the menisci) sandwiched in there on the left. So we have this large, unstable joint subject to huge forces, that we hold in biomechanically-compromised positions. Hmmmm, what could go wrong?

All joking aside, we will go into some of the ways the knee (and associated structures) can start breaking bad. Stay tuned for my series on the knee, which will hopefully be completed at a slightly less glacial pace than the shoulder! |

AuthorsDrs. Edmund Bruce-Gardner and Soraya Burrows are osteopaths Categories

All

|

|

Osteopathy at Moreland Road Clinic

High quality & personalised service from experienced professionals. A safe, effective & collaborative approach to patient care. All osteopaths undertake a 4-5 year university degree and are licensed and registered healthcare pracitioners. |

Find Us

Moreland Road Clinic 85 Moreland Road Coburg VIC 3058 P (03) 9384 0812 F (03) 9086 4194 osteopathy@morelandroadclinic.com.au |

Popular Blog Posts

|

|

|

Osteopathy at Moreland Road Clinic is on Moreland Road, near the corner of Nicholson Street/Holmes Street, on the border of Coburg, Brunswick & Thornbury.

This makes Osteopathy at Moreland Road Clinic the ideal location for people in the inner north and outer northern suburbs of Melbourne, including: Coburg, Coburg North, Coburg East, Brunswick, Brunswick East, Brunswick West, Fawkner, Oak Park, Glenroy, Preston, Pascoe Vale, Pascoe Vale South, Gowanbrae, Hadfield, Essendon, Moonee Ponds, Thornbury and Reservoir. |

26/3/2020

1 Comment